|

The Golgi complex

|

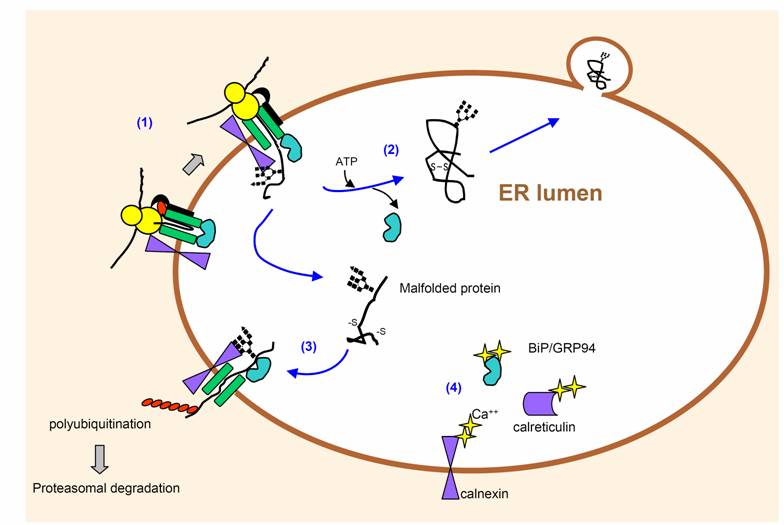

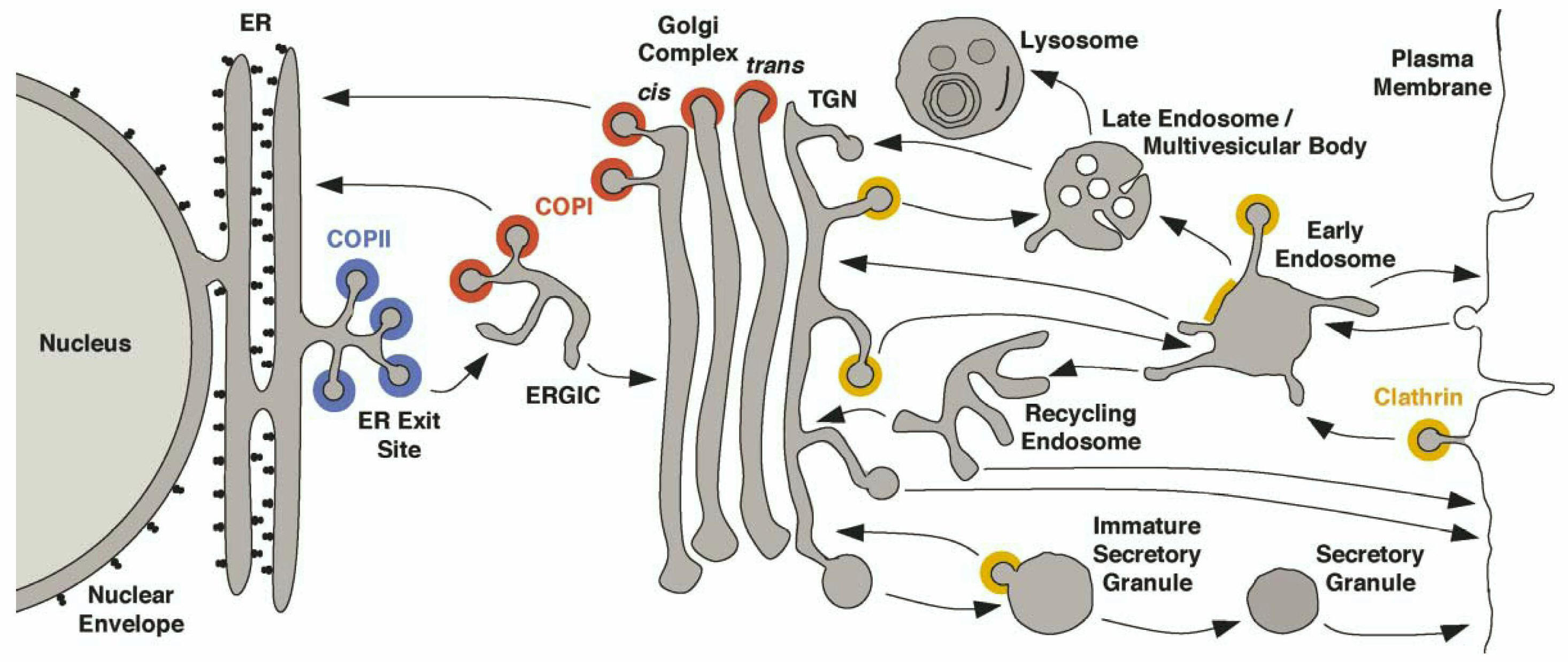

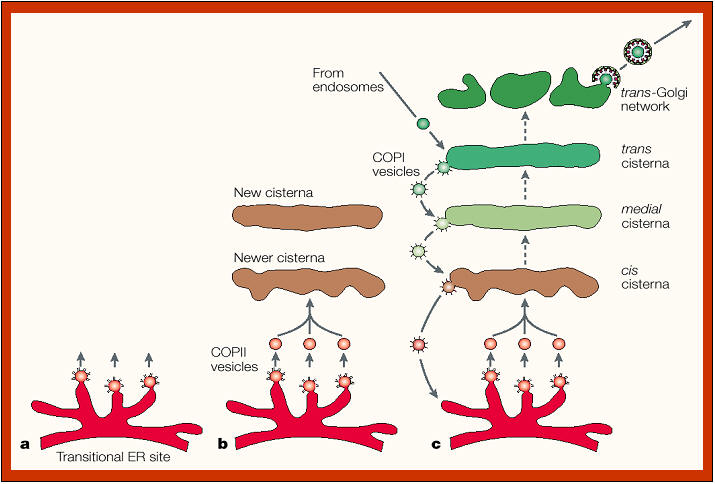

Once

secretory proteins are properly folded and modified in the first

compartment of the secretory pathway, the ER,

the proteins move to specialized regions, the ER export sites, and are packaged

in coated, irregularly shaped transport vesicles.

Following uncoating, the transport

vesicles form vesicular-tubular clusters (VTCs, also called the ER-Golgi

intermediate compartment ERGIC) that move to the Golgi.

The scheme below

depicts the compartments of the secretory pathway and two compartments

associated with the secretory pathway, namely the lysosomal/vacuolar and

endocytic pathways. Transport steps are indicated by arrows. Colors

indicate the known or presumed locations of the transport vesicle coats COPII (blue), COPI (red),

and clathrin (yellow/orange). Clathrin coats are heterogeneous and contain

different adaptor and accessory proteins at different membranes. Only

the function of COPII in ER export and of plasma membrane-associated

clathrin in endocytosis are known with certainty. Less well understood

are the exact functions of COPI at the ERGIC and Golgi complex and of

clathrin at the TGN, early endosomes, and immature secretory granules.

The pathway of transport through the Golgi stack is still being

investigated, but is generally believed to involve a combination of COPI-mediated

vesicular transport and cisternal maturation (see below). Additional coats or

coat-like complexes exist but are not represented in this figure. |

|

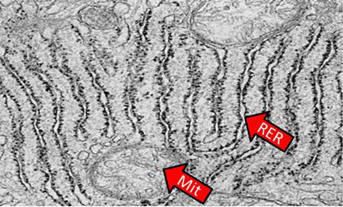

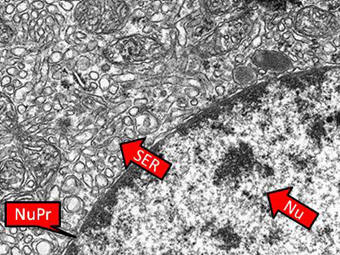

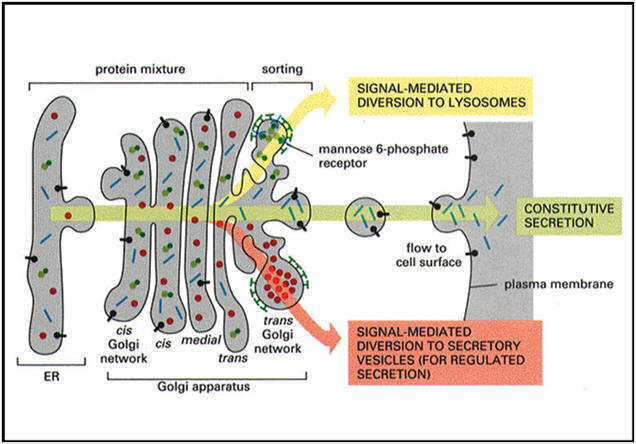

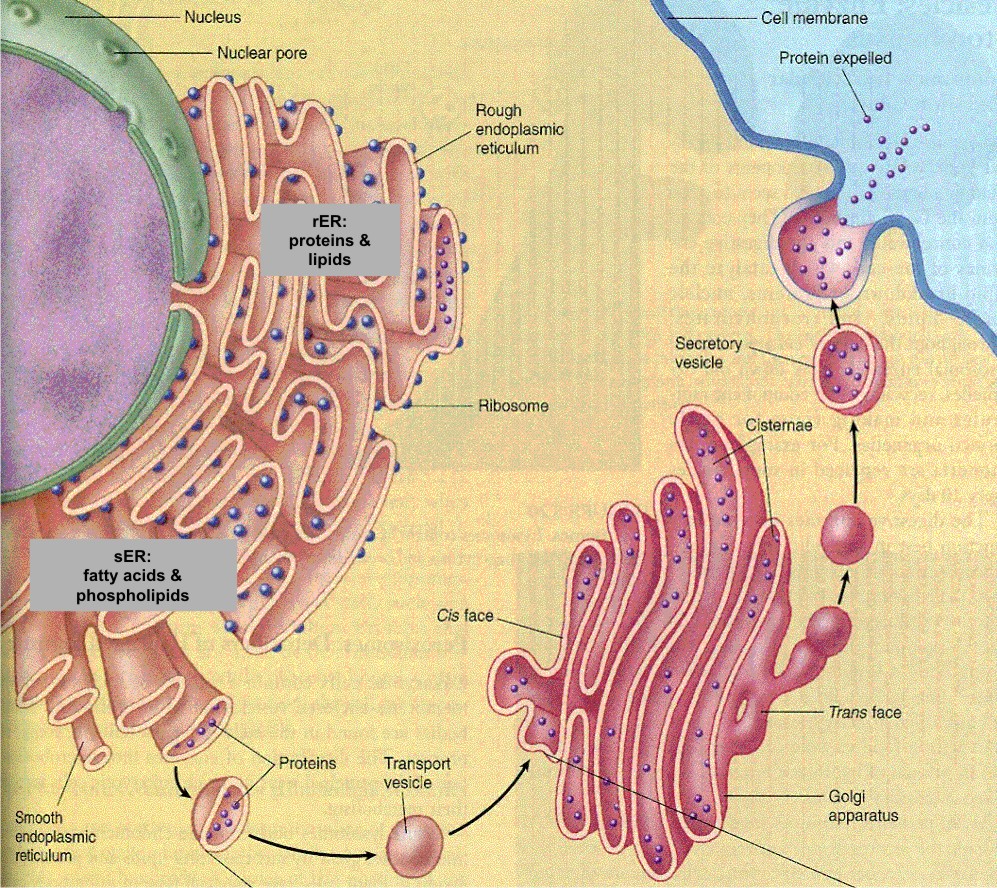

The

Golgi

apparatus

modifies

and

sorts

proteins

for

transport

throughout

the

cell.The

Golgi

apparatus

is

often

found

in

close

proximity

to

the

ER

in

cells.

Protein

cargo

moves

from

the

ER

to

the

Golgi,

is

modified

within

the

Golgi,

and

is

then

sent

to

various

destinations

in

the

cell,

including

the

lysosomes

and

the

cell

surface.

|

|

|

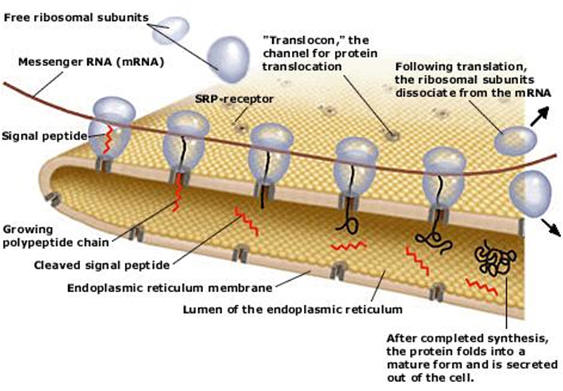

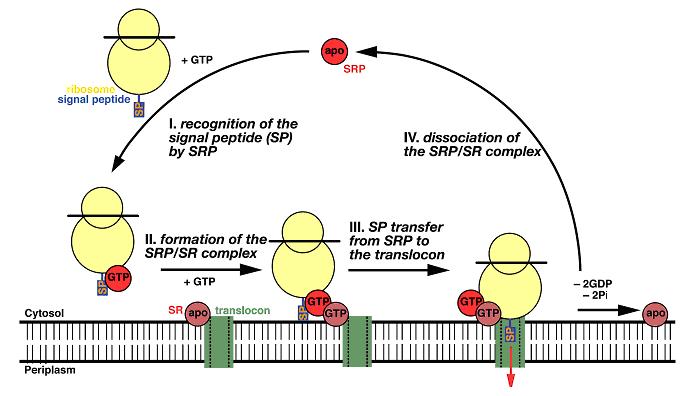

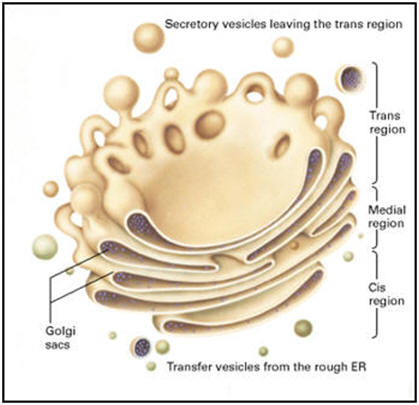

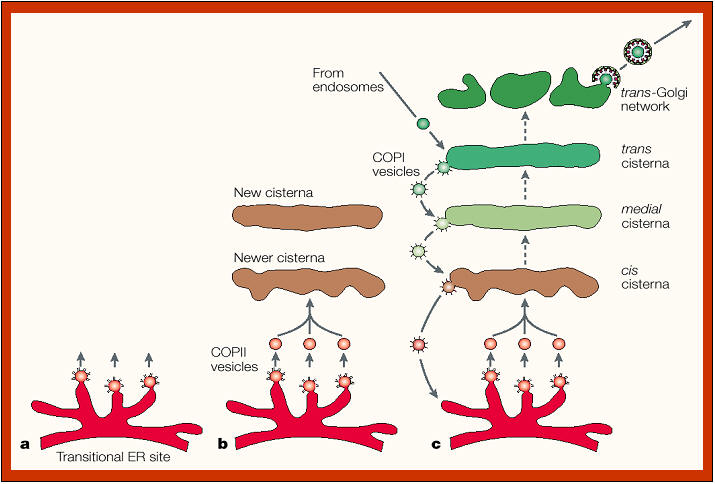

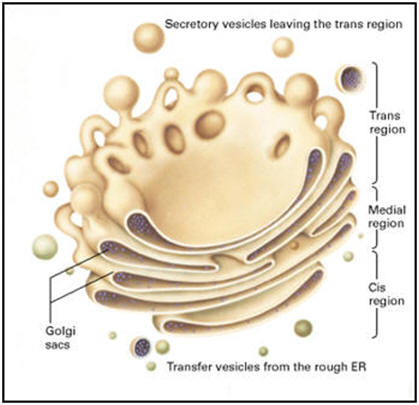

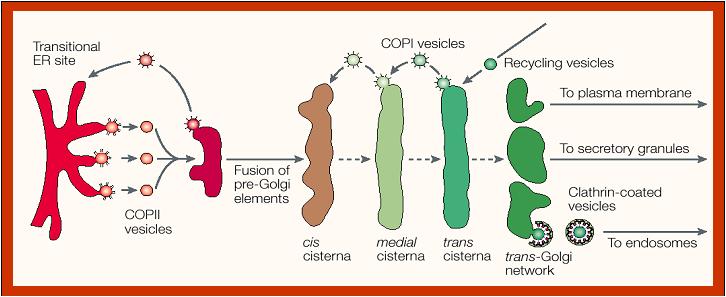

The

buds emerging from the ER thus become vesicles and are coated with COPII

protein coats. After the vesicles lose their COPII coat, they merge with

the VTCs (ERGIC) carrying the soluble and membrane proteins to the Golgi

complex. Note that the vesicles are moving to contribute to the

cis-Golgi network of vesicles and cisternae. The movement of these

special transport vesicles is an energy-requiring process. If one blocks

production of ATP, the transport will not happen. The drawing above shows how

the ER forms vesicles (without ribosomes attached) that carry the newly

synthesized proteins to the Golgi complex. The inside of the vesicle

becomes continuous with the inside of the Golgi cisternae, so that

protein groups pointing towards the inside, could eventually be directed

to face the outside of the cell. Carbohydrate groups are attached and

any subunits may be joined in these cisternae. The protein is then

passed to the final region of the Golgi called the "trans face". There

it is placed in vacuoles that bud from this region of the Golgi complex.

These may be a certain size or density, characteristic of the cell

itself. The vacuoles continue to condense the proteins and the final

mature secretory granule is then moved to the membrane for secretion.

|

|

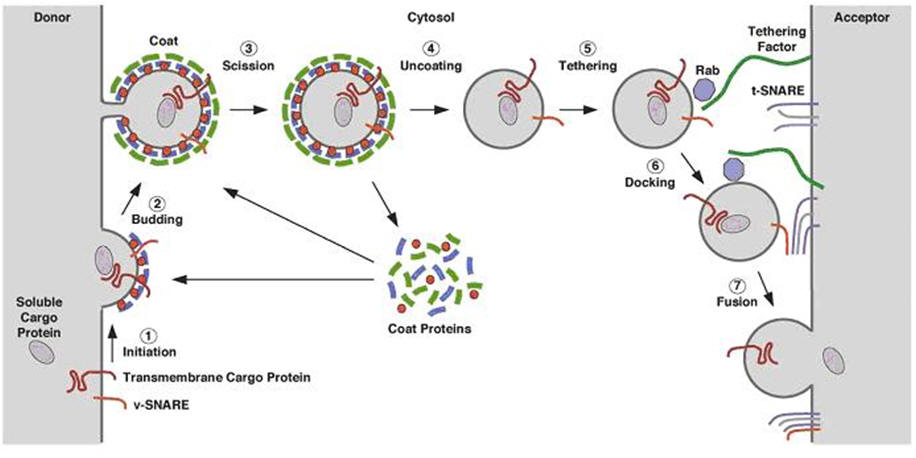

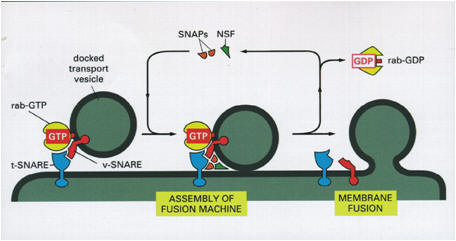

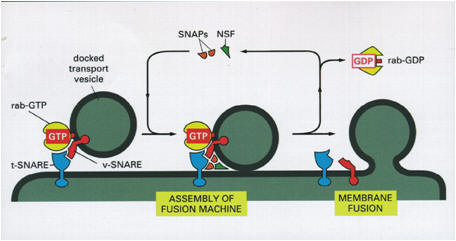

Transport of material in and out of the Golgi

complex thus involves budding and fusion of vesicles. The cartoon shows

that the membranes of each join and align themselves during the process

so that the inside face remains in the lumen and the outside face

remains towards the cytoplasm. |

|

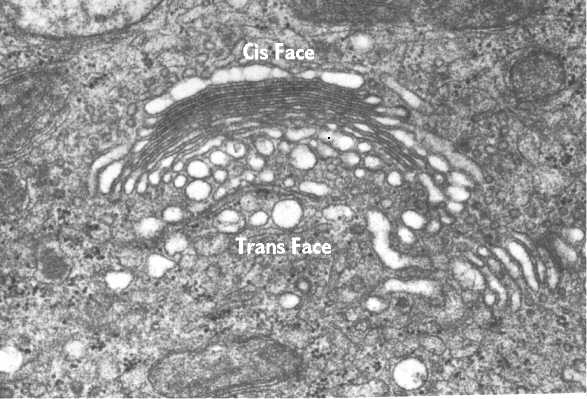

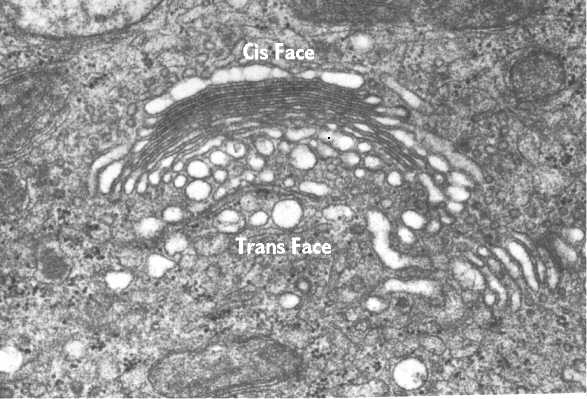

This

electron micrograph illustrates the Golgi complex. The Golgi is curved with its

trans face pointing away from the nucleus (top left) toward the cell periphery. The

numerous vesicles in the area are transporting the proteins to and from cisternae. |

|

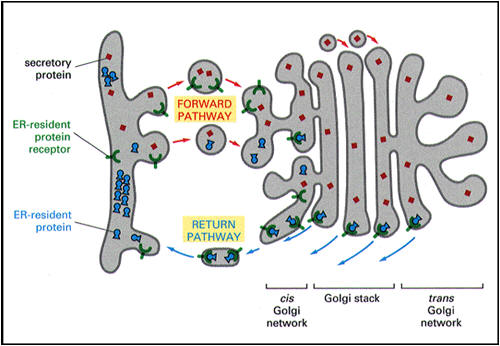

Can proteins be transported from the Golgi back to the ER?

|

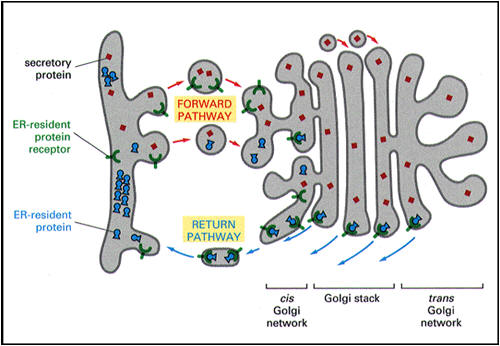

Sometimes vital proteins needed in the ER are transported along with the

other proteins to the Golgi complex. The Golgi complex has a mechanism

for trapping them and sending them back to the ER. This cartoon shows

the process. The protein destined for secretion is red (travels via the

forward or anterograde pathway). The blue protein must remain in the ER.

The ER has inserted a receptor protein on the membrane it sends to the

Golgi complex in the transitional vesicles (the so-called KDEL receptor,

shown in green). These are retrograde vesicles and are therefore coated

with COPI. The KDEL receptor captures all of the protein that

carries the ER residency signal (the KDEL signal, dot in figure on the

right, e.g., in BiP). Vesicles then bud

from the Golgi complex and move back to the ER (retrograde pathway). The

receptor can circulate and continue to return the proteins needed by the

ER. |

|

|

|

|

|

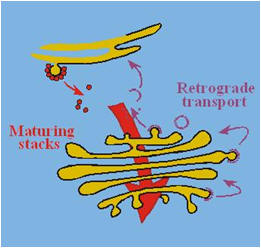

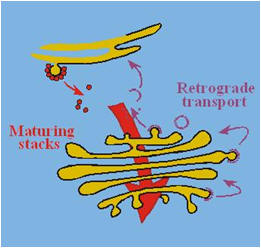

Golgi formation and cisternal

maturation

|

There is much interest in understanding how the different Golgi

cisternae are organized and differentiated. Two main models exist.

In the

“vesicular model” of protein transport (see figure above), all anterograde (forward) and

retrograde (backward) intra-Golgi steps involve transport only via

vesicles. Alternatively, a nonvesicular transport mechanism may be

present in which Golgi cisternae form at the cis-face of the stack,

probably by VTC fusion, and then progressively mature into trans-cisternae

(“cisternal maturation model”; see figures on the right and below). In this model, cisternae (or intermittent tubular continuities) carry secretory cargo

through the stack in the anterograde direction, while vesicles transport

Golgi enzymes in the retrograde direction, allowing cisternal maturation

to occur by progressive uptake of material from older stacks. At the TGN,

the cisternae ultimately disintegrate and evolve into a collection of

secretory vesicles, including immature secretory granules. |

|

|

|

|

|

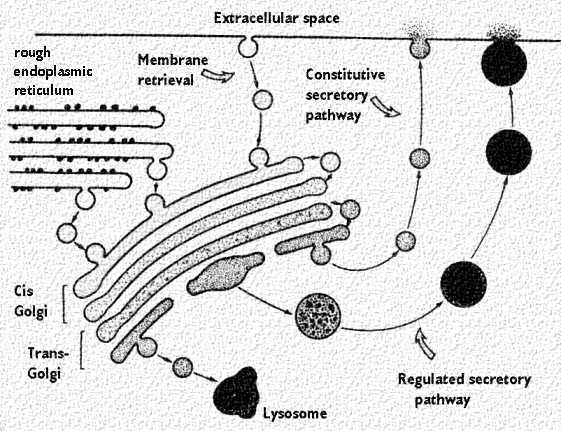

The

Golgi complex controls trafficking of different types of proteins. Some

are destined for secretion. Others are destined for the extracellular

matrix. Finally, other proteins, such as lysosomal enzymes, may need to

be sorted and sequestered from the remaining constituents because of

their potential destructive effects. The figures below show

the two types of secretory pathways. The regulated secretory pathway, as

its name implies, is a pathway for proteins that requires a stimulus or

trigger to elicit secretion. Some stimuli regulate synthesis of the

protein as well as its release. The constitutive pathway allows for

secretion of proteins that are needed outside the cell, like in the

extracellular matrix. It does not require stimuli, although growth

factors may enhance the process. Finally, the cartoons also show the

packaging of lysosomes. |

Golgi proteins

|

The Golgi apparatus

contains at least a thousand different types of integral and peripheral

membrane proteins, perhaps more than any other intracellular organelle.

The Golgi apparatus performs three major functions essential for growth,

homeostasis and division of eukaryotic cells. First, it operates as a

carbohydrate factory for the processing and modification of proteins and

lipids moving through the secretory pathway. Second, it serves as a

station for protein sorting and transport, receiving membrane from the

ER and delivering it to the plasma membrane or other intracellular

sites. Finally, it acts as a membrane scaffold onto which diverse

signaling, sorting and cytoskeleton proteins adhere.

These

distinct Golgi functions operate within a structure that is unique among

subcellular organelles in many ways, including its composition as a

stacked array of cisternae and connecting tubules/vesicles, its enormous

diversity of protein components (>1000 different types), and its

unrivaled capacity to dynamically transform in response to specific

stimuli or other cellular changes.

No class

of Golgi protein is stably associated with the Golgi. Integral membrane

proteins associated with the Golgi, including processing enzymes for

post-translational protein modification (i.e. mannosidase II, galactosyltransferase, etc), are continuously exiting

and re-entering the Golgi by membrane trafficking pathways leading to

and from the ER. Peripheral membrane proteins associated with the Golgi

exchange constantly between membrane and cytosolic pools. Newly

synthesized cargo proteins passing through the Golgi to other

destinations (which include both integral membrane and luminal proteins)

also spend relatively short periods of time in the Golgi. The residency

times for these different classes of Golgi proteins vary enormously:

Golgi processing enzymes stay for ~60 min, cargo proteins ~30 min, cargo

receptors ~10 min and peripheral proteins ~1 min.

|

|

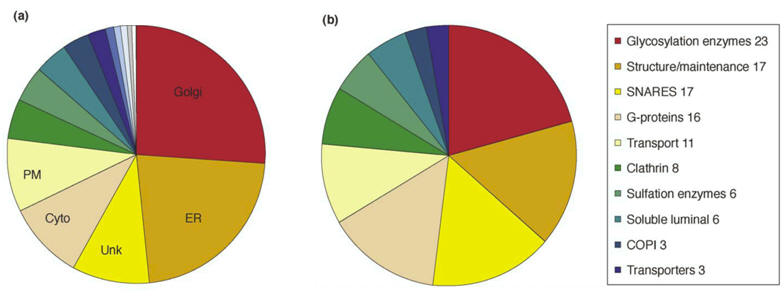

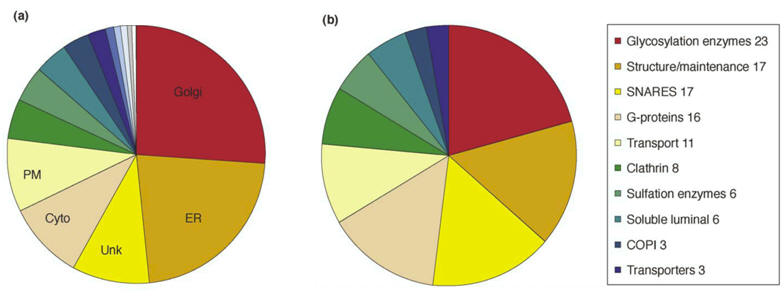

Classification of proteins identified in a rat liver Golgi proteome:

(a)

Proteins were grouped

by cellular location. Twenty-six percent of the identified proteins were

known Golgi proteins, whereas 23 percent were ER proteins. Many of the

cytosolic and cytoskeletal proteins functionally interact with the Golgi;

PM: plasma membrane, Unk: unknown.

(b)

Golgi-localized

proteins were grouped by function. |

|

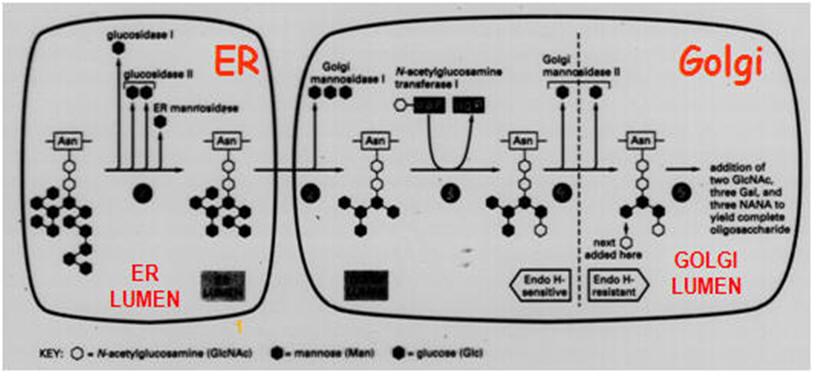

Post-translational protein modifications in the Golgi complex

|

The Golgi

complex is compartmentalized. Phosphorylation occurs in the cis region.

In other regions, different types of carbohydrates are added as a

glycoprotein passes through the cisternae. The figure on the right illustrates the

different regions where sugars like mannose (man), galactose (gal), etc

are added. The final sorting is done in the trans-Golgi complex.

Proteins of all living organisms

are generally modified in many different ways. A functionally important

posttranslational modification is the phosphorylation of proteins. The

presence or absence of a phosphate group at specific hydroxyl amino

acids regulates the activity, stability, localization, and

oligomerization of proteins and in this way influences the flow through

metabolic pathways, the transduction of external and internal signals,

as well as the timing of developmental steps. The most complex and at

the same time energetically most costly protein modification is, however,

the glycosylation of proteins. |

-

Types of sugar-peptide bonds in eukaryotes. Asn=asparagine;Ser

=serine;Thr =threonine; Hyl =hydroxylysine; Hyp =hydroxyproline; Tyr=tyrosine; GlcNAc

=N-acetylglucosamine; GalNAc =Nacetylgalactosamine; Glc

=glucose; Gal =galactose; Rha =rhamnose; Xyl=xylose; Ara =arabinose;

Man =mannose; Fuc=fucose.

|

|

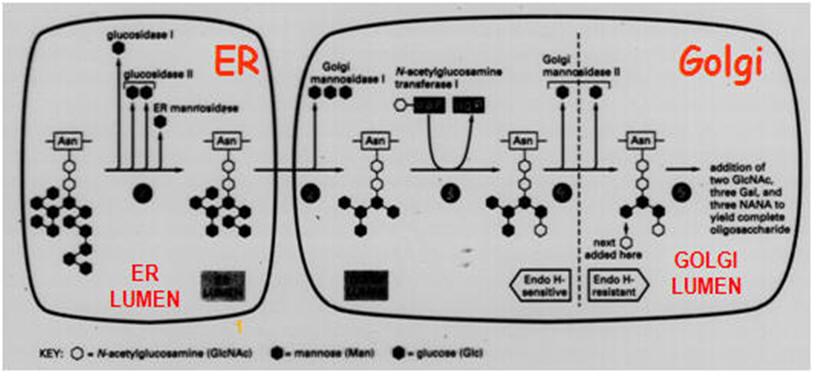

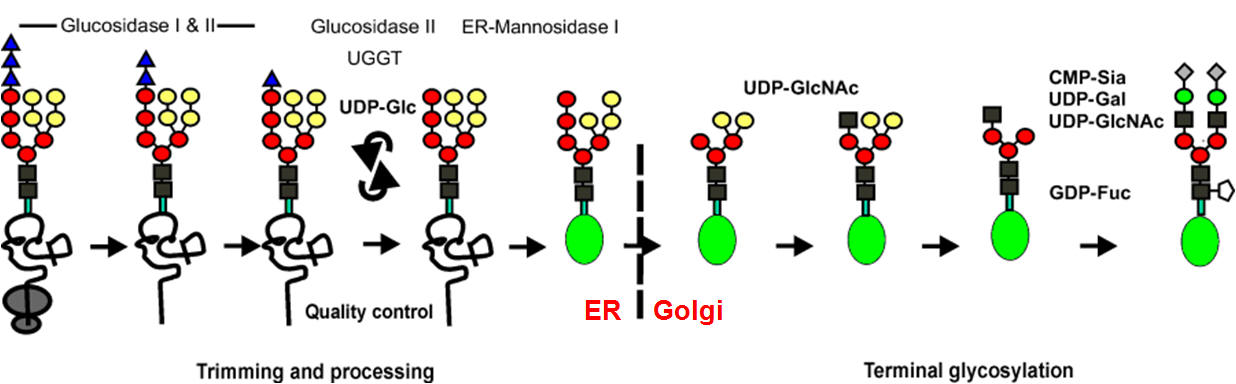

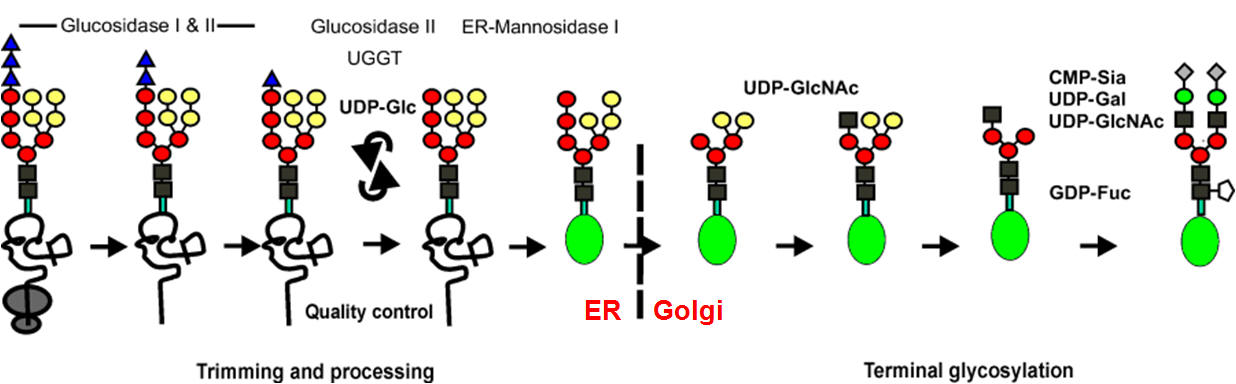

Processing and maturation of N-glycan chains

Glycoproteins are proteins containing

covalently linked oligosaccharides that consist of different monomers

and are mostly branched. The carbohydrate moiety amounts to about 20% of

the molecular weight, but can be as much as 90% in some cases. In animal

cells, glycoproteins are distinguished from proteoglycans, extracellular

proteins with mostly long, unbranched polysaccharides, consisting of

serially repeating units. The so-called N-glycosylated proteins contain

oligosaccharides that are N-glycosidically linked to the g-amido group

of asparagines. This type of glycoprotein has been most intensively

studied with respect to their structure, biosynthesis, and function.

After the first

trimming steps in the ER, the exit of the correctly folded glycoprotein

(symbolized by a green ellipse, Figure below) occurs from the ER to the Golgi apparatus

where, in a strictly defined reaction sequence, a further demannosylation takes

place, followed by transfer of a GlcNAc residue, and finally removal of two

further mannose residues. In terminal glycosylation reactions, the mature glycan

structure is built up in a protein-dependent, tissue- and organism-specific

manner. The generated glycans are classified as high-mannose-type, complex-

type, and hybrid-type glycan structures. In the Figure below, only one possible terminal

pathway is depicted leading to a biantennary-complex-type glycan chain; the

number of antennae may vary up to six. In the case of soluble, lysosomal

glycoproteins, a mannose-6-phosphate determinant is generated that functions as

the signal for targeting the protein to the lysosome.

The many

different sugars, which are either N- or O-glycosidically linked to the

amino acid asparagine or to the hydroxy amino acids threonine, serine,

hydroxyproline, hydroxylysine, and tyrosine, reflect

the complexity of protein glycosylation. Protein

N-glycosylation and protein O-mannosylation are evolutionarily conserved

from yeast to man. In addition, there is a large

variety of more or less highly branched oligo- and polysaccharides of

varying composition that are linked to the proximal sugar of the

protein. The functional importance of protein glycosylation, however,

remained poorly understood for a long time, apart from the role of

saccharides as blood-group antigens. Only within the last few years

has it become increasingly evident that the lack of individual glycosyl

transferases contributing to the synthesis of sugar “trees” of specific

proteins can cause most severe congenital diseases in children,

including the CDG syndrome (congenital disorders of glycosylation) as

well as congenital muscular dystrophies with neuronal-cell-migration

defects. Although

the molecular details leading to these diseases are only vaguely

understood, it seems clear that sugar components of proteins play a

major role in embryonic and postembryonic development of humans as well

as of all higher eukaryotes.

|

|

|

|

Glycoproteins processed by the Golgi apparatus, illustrating species

variation. |

See the movies "Protein

trafficking in the Golgi", "Protein

modifications in the Golgi", "Constitutive

secretion" and "Regulated

secretion" (use Quicktime).

Golgi maintenance and

biogenesis

The

Golgi apparatus contains thousands of different types of integral and

peripheral membrane proteins, perhaps more than any other intracellular

organelle. To understand these proteins' roles in Golgi function and in

broader cellular processes, it is useful to categorize them according to

their contribution to Golgi creation and maintenance. This is because

all of the Golgi's functions derive from its ability to maintain

steady-state pools of particular proteins and lipids, which in turn

relies on the Golgi's dynamic character - that is, its ongoing state of

transformation and outgrowth from the ER.

The Golgi

apparatus performs three major functions essential for growth,

homeostasis and division of eukaryotic cells. First, it operates as a

carbohydrate factory for the processing and modification of proteins and

lipids moving through the secretory pathway. Second, it serves as a

station for protein sorting and transport, receiving membrane from the

ER and delivering it to the plasma membrane or other intracellular

sites. Finally, it acts as a membrane scaffold onto which diverse

signaling, sorting and cytoskeleton proteins adhere.

These distinct

Golgi functions operate within a structure that is unique among

subcellular organelles in many ways, including its composition as a

stacked array of cisternae and connecting tubules/vesicles, its enormous

diversity of protein components (>1000 different types), and its

unrivaled capacity to dynamically transform in response to specific

stimuli or other cellular changes. Examples of the Golgi’s dynamic

behavior include its reversible disassembly during mitosis and under

experimentally induced conditions (e.g. osmotic stress or treatment with

BFA, Exo1 or ilimaquinone), and its rebuilding at peripheral ER export

sites in response to microtubule disruption or expression of mutated

proteins that function in ER-to-Golgi trafficking.

The Golgi’s

ability to transform itself fundamentally under different conditions is

probably due to the fact that proteins only associate with it

transiently as they move through other pathways in the cell. Conditions

that alter the entry or return of these proteins to the Golgi,

therefore, will disrupt Golgi structure and function. Also, many

proteins associated with the Golgi are part of large protein complexes.

Altering the association of one protein in the complex may affect the

stability and localization of others, with downstream consequences for

Golgi organization and structure.

Integral

membrane proteins associated with the Golgi are continuously exiting and

re-entering the Golgi by membrane trafficking pathways leading to and

from the ER. Peripheral membrane proteins associated with the Golgi, by

contrast, exchange constantly between membrane and cytosolic pools.

Newly synthesized cargo proteins passing through the Golgi to other

destinations (which include both integral membrane and luminal proteins)

also spend relatively short periods of time in the Golgi. The residency

times for these different classes of Golgi proteins vary enormously:

Golgi processing enzymes stay for ~60 min, cargo proteins ~30 min, cargo

receptors ~10 min and peripheral proteins ~1 min.

Post-translational

modifications of prohormones

In

addition to glycosylation and phosphorylation in the early stages of the

secretory pathway, a secretory protein can undergo sulfation at

carbohydrate side chains or tyrosine residues in the late pathway (by

carbohydrate and tyrosylprotein sulfotransferases,

respectively). Furthermore, the protein can undergo proteolytic

cleavage. The first step in proprotein proteolytic processing is usually

an endoproteolytic cleavage in the trans-Golgi network (TGN) or

immature secretory granule (ISG) on the carboxy-terminal

side of a recognition site, often a pair of basic amino acids and mostly

Lys-Arg or Arg-Arg. The proprotein processing enzymes are calcium- and

pH-dependent serine endoproteases related to the bacterial proteolytic

enzyme subtilisin and are called proprotein convertases (PCs). These

enzymes are structurally related (strongest in their active sites) and

form a gene family consisting of at least seven members, including furin

(also called PACE, Paired basic Amino acid residue Cleaving Enzyme), the

prohormone convertases PC1/PC3 and PC2, and (in yeast) KEX2. Furin and

KEX2 are active in constitutively secreting cells. The neuroendocrine-specific

enzymes PC1/PC3 and PC2 cleave prohormones and are selectively present

in cells equipped with the regulated secretory pathway. A differential

expression of PC1/PC3 and PC2 may result in a different secretory output

from endocrine and neuronal cells. Furthermore, a single prohormone may

give rise to multiple peptide hormones with a variety of bioactivities.

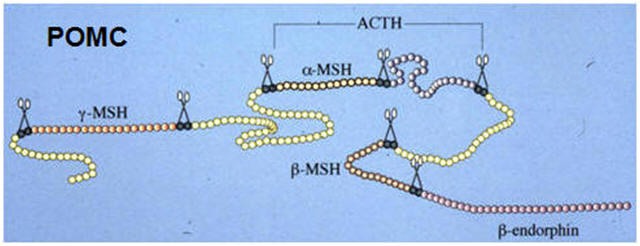

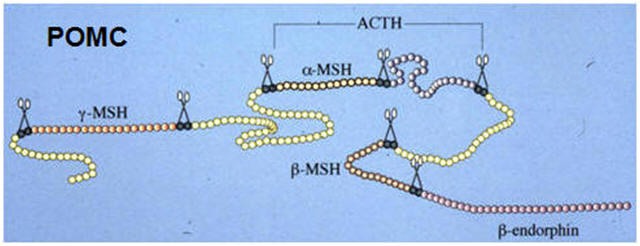

For example, processing of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) can result in

a-,

b- and

g-melanocyte-stimulating

hormones (MSHs), the stress hormone adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) and the

endorphins, peptides with endogenous opiate-like activity. POMC cleavage

by the PC1/PC3 enzyme generates ACTH, whereas PC2 produces the MSHs and

endorphins. PCs become active by autocatalytic cleavage of an

amino-terminal propeptide that may act as an intramolecular chaperone

for proenzyme folding. The 7B2 protein has been found to act as a

chaperone specific for PC2 by transiently interacting with the proenzyme

form, facilitating proPC2 transport and activation. The proSAAS protein,

with a structural organization similar to 7B2, appears to have PC1/PC3

as its major intracellular binding target. The proper acidic environment

in the subcompartments of the secretory pathway, essential for optimal

PC cleavage activity, is supplied by a H+-pumping

vacuolar-type ATPase (V-ATPase). Following cleavage by PCs,

exoproteolytic removal of the exposed carboxy-terminal basic residues

occurs by the enzyme carboxypeptidase E (or KEX1 in yeast). Finally,

the generated peptide may undergo one or two modifications that are

crucial for its biological activity, namely acetylation at the amino

terminus and amidation at the carboxy terminus if the peptide ends in

glycine (by the enzyme Peptidyl-glycine-α-Amidating

Monooxygenase, PAM). |

|

|

Proteolytic processing of the prohormones proinsulin and

proopiomelanocortin (POMC) |

|

Exocytosis

and endocytosis

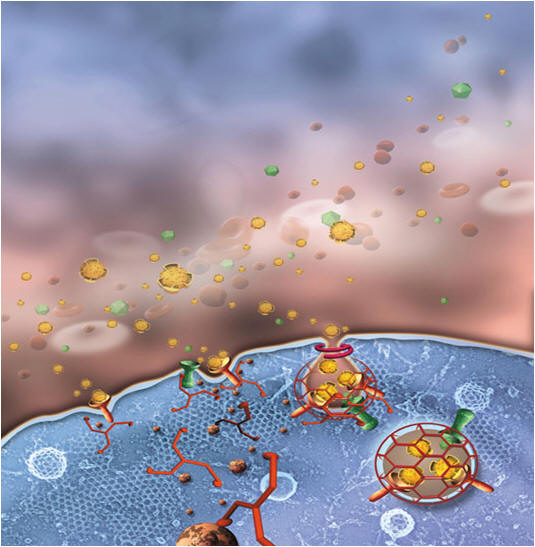

Secretory proteins are released into the

extracellular space by exocytosis, a process involving the fusion of the

secretory granule membrane with the cell membrane. For the two types of

exocytosis, namely regulated (triggered) and constitutive (untriggered)

exocytosis, regulatory mechanisms of membrane fusion might be quite

different. Regulated exocytosis is coupled in most cases with

endocytosis to provide a membrane shuttle in order to prevent that the

plasma membrane would become too large which would occur when only

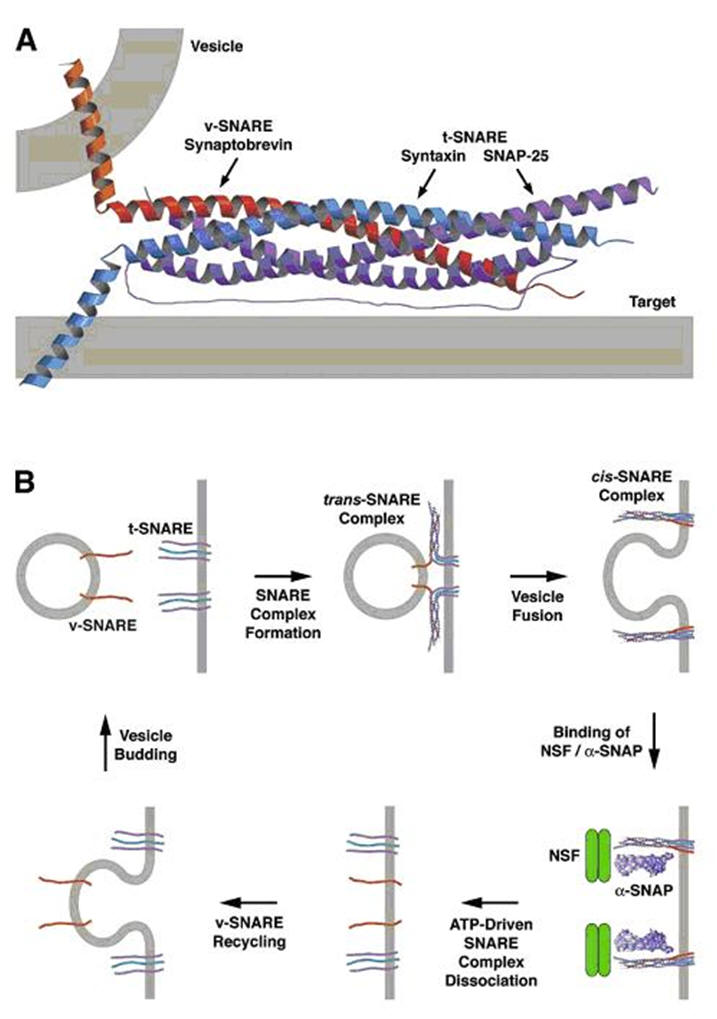

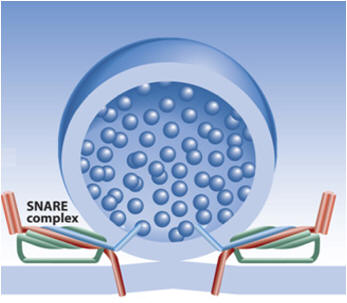

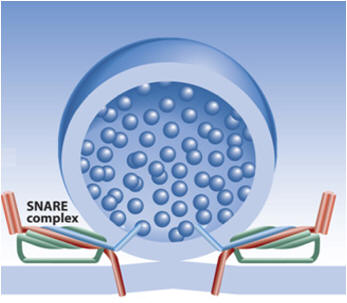

exocytotic events take place. A number of components of the exocytotic

and endocytotic machinery has been recently isolated and identified,

e.g. synaptophysin, synaptotagmin, synaptobrevin (VAMP), syntaxin and

annexins.

Exocytosis

Exocytosis is

thus the process whereby intracellular fluid-filled vesicles fuse with

the plasma membrane (PM), incorporating vesicle proteins and lipids into

the plasma membrane and releasing vesicle contents into the

extracellular milieu. This membrane fusion event thus mediates the

targeting of proteins and lipids to the PM and the secretion of

molecules from the cell. Exocytosis can occur constitutively or can be

tightly regulated, for example, neurotransmitter release from nerve

endings. The last two decades have witnessed the identification of a

vast array of proteins and protein complexes essential for exocytosis.

As mentioned above, SNARE proteins are probable mediators of membrane

fusion, whereas other proteins function as essential SNARE regulators. A

central question that remains unanswered is how exocytic proteins and

protein complexes are spatially regulated.

Constitutive

exocytosis events include the fusion of vesicles derived from the

trans-Golgi network (TGN) with the PM, which is essential for the

insertion of newly synthesized proteins and lipids into the PM.

Polarized cells have developed specialized mechanisms for the targeting

of these TGN-derived vesicles to specific regions of the PM, for

example, apical vs. basolateral membrane in polarized epithelial cells.

In addition, proteins that are constitutively recycled through the

endosomal system, such as the transferrin receptor, are transported to

the cell surface via the fusion of endosomal vesicles with the PM. These

constitutive pathways operate in all cells. In addition, a number of

cell types undergo a more specialized form of exocytosis known as

regulated exocytosis. Exocytosis of regulated secretory vesicles only

occurs upon receipt of a specific stimulus, such as exocytosis of

synaptic vesicles in nerve cells. In the majority of cases, regulated

exocytosis is stimulated by a local and transient increase in calcium

levels.

Exocytosis can

involve the full fusion of a vesicle with the PM or, in more specialized

cases such as regulated exocytosis from neuronal and neuroendocrine

cells, can also occur by a "kiss-and-run" mechanism. Kiss-and-run

exocytosis involves the formation of a transient fusion pore that allows

release of a limited amount of the vesicle content before the pore

re-seals and the vesicle is released from the plasma membrane.

The study of

regulated exocytosis at the molecular level has been driven by a number

of key questions: How are vesicles recruited to the PM? What proteins

anchor vesicles to the PM? What proteins sense and respond to elevated

calcium levels? What proteins initiate and catalyze membrane fusion?

Finally, how are all these proteins regulated? These questions have led

to the identification of numerous proteins, each with their own

intricate contribution to exocytosis (see figure). The high efficiency of the

exocytosis machinery is exemplified in the ultra-fast response it can

exhibit to appropriate stimuli; for example, synaptic vesicles can fuse

with the presynaptic PM microseconds following calcium influx.

Lipid

rafts:

membrane platforms regulating intracellular pathways

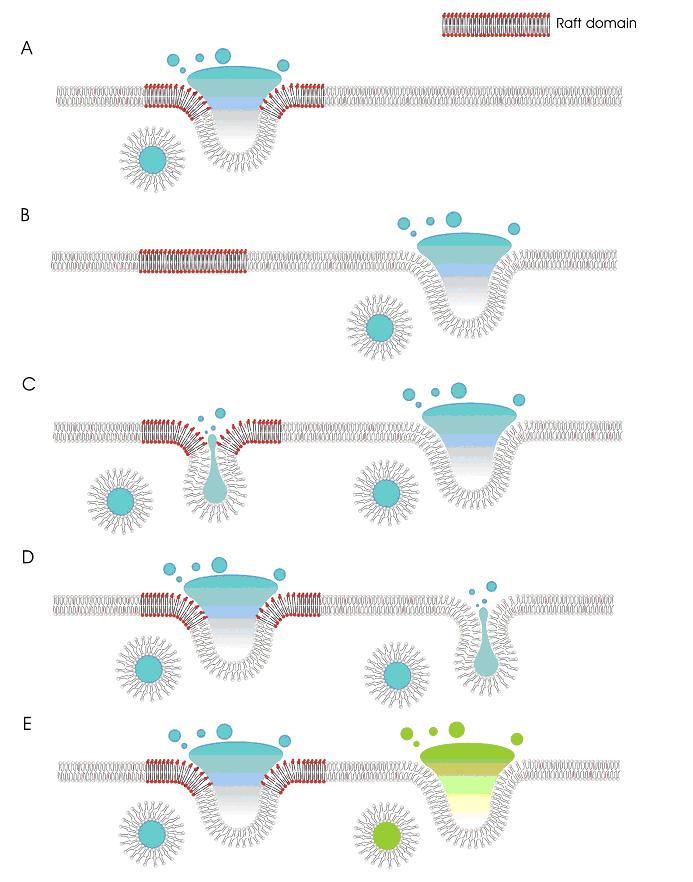

Recent studies suggest that lipid

rafts, cholesterol and sphingolipid-rich microdomains, enriched in the

plasma membrane, play an essential role in regulated exocytosis

pathways. The association of SNAREs with lipid rafts acts to concentrate

these proteins at defined sites of the plasma membrane. Furthermore,

cholesterol depletion inhibits regulated exocytosis, suggesting that

lipid raft domains play a key role in the regulation of exocytosis. The

role of lipid rafts in regulated exocytosis can vary from a passive role

as spatial coordinator of exocytic proteins to a direct role in the

membrane fusion reaction.

The lipids that

compose cellular membranes are diverse, and as such have different

affinities towards proteins and other lipids. The lipid "raft"

hypothesis suggests that sphingolipids and cholesterol cluster into

discrete regions of the cell membrane. These sphingolipid- and

cholesterol-rich domains have been termed lipid "rafts" because they

exist in a less fluid and more ordered state than glycerophospholipid-rich

domains of the membrane. Studies on model membranes clearly demonstrate

clustering and segregation of sphingolipids, cholesterol and certain

types of glycerophospholipids, and there is now also evidence that

raft-type domains exist in living cells.

Lipid rafts are

resistant to solubilization by cold nonionic detergents; this resistance

has been used as the criterion for raft purification from numerous cell

types, and has allowed a detailed analysis of raft function in various

cellular pathways. The term "lipid raft" thus refers to membrane domains

that are resistant to detergent extraction. In addition to the

characterization of detergent-insoluble lipid rafts, fluorescent imaging

techniques such as fluorescence energy transfer and patching/co-patching

of membrane proteins have provided essential data on the domain

structure of the plasma membrane in fixed and living cells.

The ability of

lipid rafts to sequester specific proteins and to exclude others makes

them ideally suited to spatially organize cellular pathways. Rafts have

been implicated in the regulation of a range of signal transduction

pathways, where raft association of components of a signaling cascade

likely facilitates protein protein interactions and signal amplification.

Rafts have also been implicated in membrane traffic pathways, such as

the formation of regulated and constitutive secretory vesicles. protein interactions and signal amplification.

Rafts have also been implicated in membrane traffic pathways, such as

the formation of regulated and constitutive secretory vesicles.

Evidence that

lipid rafts play a key role in regulated exocytosis has emerged from a

number of recent studies examining the membrane domain distribution of

SNARE proteins. The conclusions form these studies:

SNARE proteins are clustered in the plasma membrane in a

cholesterol-dependent manner; a proportion of these cholesterol-rich

clusters correspond to lipid raft domains - the amount of SNAREs in

lipid raft domains depends upon the specific SNARE isoform and the cell

type; the integrity of lipid raft domains is important for exocytosis.

Rafts and

the regulation of membrane fusion and exocytosis

If SNAREs are

localized in different domains at the plasma membrane, what does this

mean for membrane fusion? Specifically, do the SNARE clusters in lipid

rafts or nonrafts mark the sites of exocytosis? Further analyses will

hopefully address whether regulated exocytosis occurs at specific

SNARE clusters and determine the molecular characteristics of these

fusion-competent domains.

The

different protein and lipid composition of lipid rafts and nonraft

domains is likely to impact directly on membrane fusion and exocytosis.

There are a number of possibilities for how lipid rafts may function in

regulated exocytosis (Figure 5): The protein/lipid composition of rafts

is conducive to exocytosis, whereas membrane fusion in nonraft domains

is prevented (Figure 5A). The figure depicts fusion in the middle of the

lipid raft domain; alternatively, membrane fusion may occur at the edges

of raft domains, or rafts may surround the fusion site. Fusion occurs

exclusively in nonraft domains (Figure 5B). Lipid rafts and nonraft

domains support different types of exocytosis, for example full fusion

vs. kiss-and-run exocytosis. In the latter form of exocytosis, a

transient fusion pore is formed, allowing release of vesicle contents;

this fusion pore then quickly seals and the vesicle is released from the

plasma membrane. The lipid composition of rafts and nonraft domains may

favor one of these exocytic events (Figure 5C,D). Raft and nonraft

domains may also regulate the fusion of specific vesicle pools (Figure

5E) |

|

|

|