Primary structure of proteins

The primary structure of peptides and proteins refers to the linear number and order of the amino acids present. The convention for the designation of the order of amino acids is that the N-terminal end (i.e. the end bearing the residue with the free α-amino group) is to the left (and the number 1 amino acid) and the C-terminal end (i.e. the end with the residue containing a free α-carboxyl group) is to the right.

Secondary structure in proteins

The ordered array of amino acids in a protein confer regular conformational forms upon that protein. These conformations constitute the secondary structures of a protein. In general proteins fold into two broad classes of structure termed, globular proteins or fibrous proteins. Globular proteins are compactly folded and coiled, whereas, fibrous proteins are more filamentous or elongated. It is the partial double-bond character of the peptide bond that defines the conformations a polypeptide chain may assume. Within a single protein different regions of the polypeptide chain may assume different conformations determined by the primary sequence of the amino acids.

The α-Helix

The α-helix is a common secondary structure encountered in proteins of the globular class. The formation of the α-helix is spontaneous and is stabilized by H-bonding between amide nitrogens and carbonyl carbons of peptide bonds spaced four residues apart. This orientation of H-bonding produces a helical coiling of the peptide backbone such that the R-groups lie on the exterior of the helix and perpendicular to its axis.

Not all amino acids favor the formation of the (α-helix due to steric constraints of the R-groups. Amino acids such as A, D, E, I, L and M favor the formation of α-helices, whereas, G and P favor disruption of the helix. This is particularly true for P since it is a pyrrolidine based imino acid (HN=) whose structure significantly restricts movement about the peptide bond in which it is present, thereby, interfering with extension of the helix. The disruption of the helix is important as it introduces additional folding of the polypeptide backbone to allow the formation of globular proteins.

β-Sheets

Whereas an α-helix is composed of a single linear array of helically disposed amino acids, β-sheets are composed of 2 or more different regions of stretches of at least 5-10 amino acids. The folding and alignment of stretches of the polypeptide backbone aside one another to form β-sheets is stabilized by H-bonding between amide nitrogens and carbonyl carbons. However, the H-bonding residues are present in adjacently opposed stretches of the polypetide backbone as opposed to a linearly contiguous region of the backbone in the α-helix. β-sheets are said to be pleated. This is due to positioning of the α-carbons of the peptide bond which alternates above and below the plane of the sheet. β-sheets are either parallel or antiparallel. In parallel sheets adjacent peptide chains proceed in the same direction (i.e. the direction of N-terminal to C-terminal ends is the same), whereas, in antiparallel sheets adjacent chains are aligned in opposite directions. β-sheets can be depicted in ball and stick format or as ribbons in certain protein formats.

Super-Secondary Structure

Some proteins contain an ordered organization of secondary structures that form distinct functional domains or structural motifs. Examples include the helix-turn-helix domain of bacterial proteins that regulate transcription and the leucine zipper, helix-loop-helix and zinc finger domains of eukaryotic transcriptional regulators. These domains are termed super-secondary structures.

Tertiary structure of proteins

Tertiary structure refers to the complete three-dimensional structure of the polypeptide units of a given protein. Included in this description is the spatial relationship of different secondary structures to one another within a polypeptide chain and how these secondary structures themselves fold into the three-dimensional form of the protein. Secondary structures of proteins often constitute distinct domains. Therefore, tertiary structure also describes the relationship of different domains to one another within a protein. The interactions of different domains is governed by several forces: These include hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic interactions and van der Waals forces.

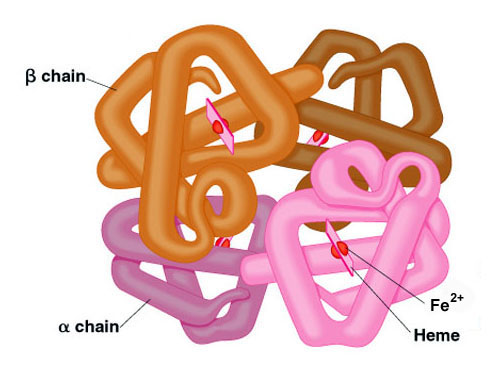

Quaternary structure

Many proteins contain 2 or more different polypeptide chains that are held in association by the same non-covalent forces that stabilize the tertiary structures of proteins. Proteins with multiple polypetide chains are oligomeric proteins. The structure formed by monomer-monomer interaction in an oligomeric protein is known as quaternary structure. Oligomeric proteins can be composed of multiple identical polypeptide chains or multiple distinct polypeptide chains. Proteins with identical subunits are termed homo-oligomers. Proteins containing several distinct polypeptide chains are termed hetero-oligomers. Hemoglobin, the oxygen carrying protein of the blood, contains two α and two β subunits arranged with a quaternary structure in the form, α2β2. Hemoglobin is, therefore, a hetero-oligomeric protein.

Structure

of hemoglobin

Structure

of hemoglobin

Complex protein structures

Proteins also are found to be covalently conjugated with carbohydrates. These modifications occur following the synthesis (translation) of proteins and are, therefore, termed post-translational modifications. These forms of modification impart specialized functions upon the resultant proteins. Proteins covalently associated with carbohydrates are termed glycoproteins. Glycoproteins are of two classes, N-linked and O-linked, referring to the site of covalent attachment of the sugar moieties. N-linked sugars are attached to the amide nitrogen of the R-group of asparagine; O-linked sugars are attached to the hydroxyl groups of either serine or threonine and occasionally to the hydroxyl group of the modified amino acid, hydroxylysine. There are extremely important glycoproteins found on the surface of erythrocytes. It is the variability in the composition of the carbohydrate portions of many glycoproteins and glycolipids of erythrocytes that determines blood group specificities. There are at least 100 blood group determinants, most of which are due to carbohydrate differences. The most common blood groups, A, B, and O, are specified by the activity of specific gene products whose activities are to incorporate distinct sugar groups onto RBC membrane glycoshpingolipids as well as secreted glycoproteins. Structural complexes involving protein associated with lipid via noncovalent interactions are termed lipoproteins. The distinct roles of lipoproteins are described on the linked page. Their major function in the body is to aid in the storage transport of lipid and cholesterol.