|

MOLECULAR & CELLULAR

NEUROBIOLOGY

Master Course Cognitive Neuroscience - Radboud

University, Nijmegen

|

|

|

|

Chapter 2: Cells and within cells |

|

|

More on DNA

|

|

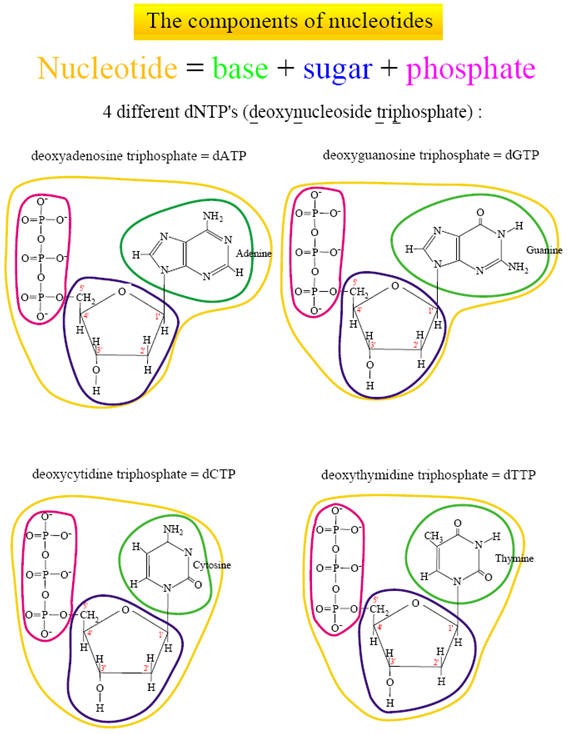

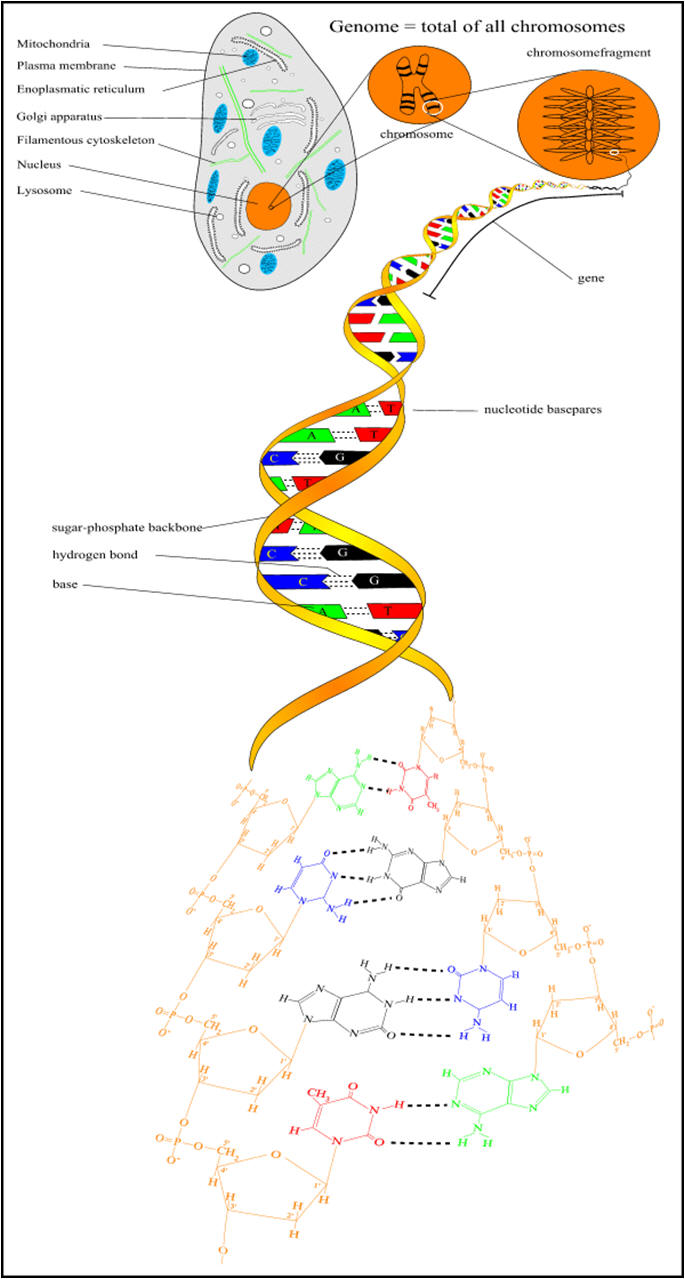

Understanding DNA: the molecule of life We already saw that the DNA molecule is a linear polynucleotide consisting of repeating units of nucleotides; nucleotides are the building stones of DNA. Each nucleotide consists of one base, a deoxyribose sugar, and a phosphate molecule. There are four bases: adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine. Adenine and guanine are purines and cytosine and thymine are pyrimidine bases. Each base is bound to one sugar and one phosphorous molecule. The ribose molecule lacks a hydroxyl group (OH) at the number 2 carbon on the ring and thus the designation deoxyribonucleic acid. The purine bases (adenine and quanine) are two-ringed structures and the pyrimidine bases (thymidine and cytosine) are the single-ringed structures (Fig 1). |

|

|

Figure 1. Building blocks of nucleic acids, DNA comprises a deoxyribose sugar backbone with the nucleotide bases adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymidine attached to the C1 position carbon on the sugar ring. |

|

There are four different nucleotides :

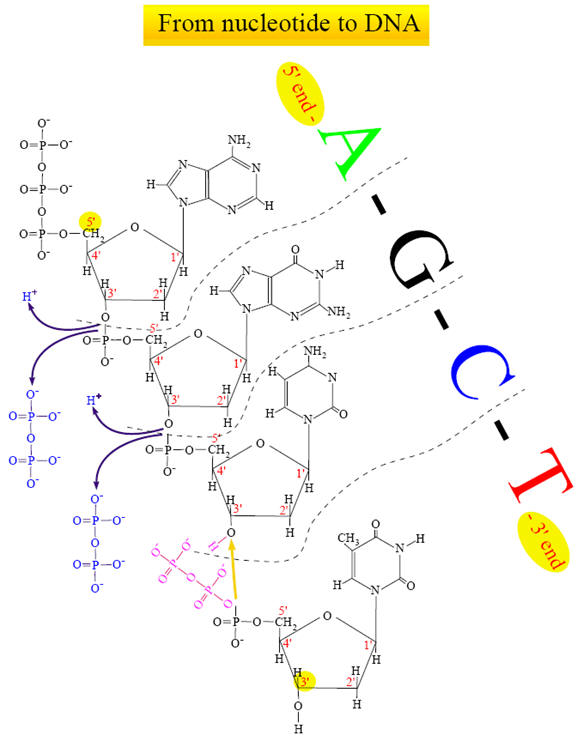

For convenience, these four nucleotides are called dNTPs (deoxynucleoside triphosphates). A nucleotide is thus made of three major parts: a nitrogen-containing base, a sugar molecule and a triphosphate. Only the nitrogen base is different in the four nucleotides. DNA is formed by coupling the nucleotides between the phosphate group from a nucleotide (which is positioned on the 5th C-atom of the sugar molecule) with the hydroxyl on the 3rd C-atom on the sugar molecule of the previous nucleotide. To accomplish this, a diphosphate molecule is split off (and releases energy). This means that new nucleotides are always added on the 3' side of the chain.

|

|

|

|

|

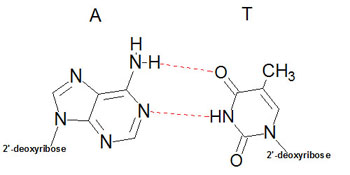

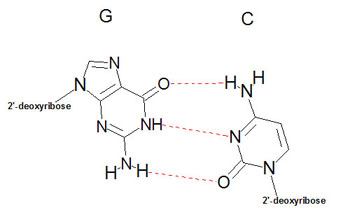

Structure of DNAUtilizing X-ray diffraction data, obtained from crystals of DNA, James Watson and Francis Crick proposed a model for the structure of DNA. This model (subsequently verified by additional data) predicted that DNA would exist as a helix of two complementary antiparallel strands, wound around each other in a rightward direction and stabilized by H-bonding between bases in adjacent strands. In the Watson-Crick model, the bases are in the interior of the helix aligned at a nearly 90 degree angle relative to the axis of the helix. Purine bases form hydrogen bonds with pyrimidines, in the crucial phenomenon of base pairing. Experimental determination has shown that, in any given molecule of DNA, the concentration of adenine (A) is equal to thymine (T) and the concentration of cytidine (C) is equal to guanine (G). This means that A will only base-pair with T, and C with G. According to this pattern, known as Watson-Crick base-pairing, .

The double-helix structure thus arises from the complementary pairing between the purine base of one strand and the pyrimidine base of the second strand. The complementary pairing is optimally stabilized by the hydrogen bonds formed between the purine and the pyrimidine base, such that guanine (G) will always pair with cytosine (C) via three hydrogen bonds and adenine (A) will always pair with thymidine (T) via two hydrogen bonds (Fig 2). The base-pairs composed of G and C thus contain three H-bonds, whereas those of A and T contain two H-bonds. This makes G-C base-pairs more stable than A-T base-pairs. Because of incompatible ring conformations, cross pairing between the other purines and pyrimidines, ie, adenine with guanine and cytosine with thymine, do not occur. This complementary base pairing is the basis of molecular genetics. The binding of a phosphorus molecule to each nucleoside gives rise to a nucleotide. When each nucleotide strand is considered individually, the sequence of nucleotide bases is always read from left to right from the 5′ carbon to 3′ carbon direction (Fig 3). In the double-helix configuration, the strand complementary to the 5′ to 3′ strand is oriented in a 3′ to 5′ direction relative to its complementary strand. This organization is referred to as the antiparallel or antisense arrangement of the DNA strands. For example, nucleotide pairing between a nucleotide strand with a 5′ ATCCG 3′ sequence has as its complementary strand 3′ TAGGC 5′ in the double-helix configuration. Additionally, when describing segments of DNA, it is common to refer to them by size. For example, a segment of double-stranded DNA composed of 200 nucleotides is often referred to as a 200-basepair (bp) segment. Similarly, 1000- and 1,000,000-nucleotide segments are 1-kb or 1000-kbp [1-megabase (Mb)] segments. The antiparallel nature of the helix thus stems from the orientation of the individual strands: from any fixed position in the helix, one strand is oriented in the 5'—>3' direction and the other in the 3'—>5' direction. On its exterior surface, the double helix of DNA contains two deep grooves between the ribose-phosphate chains. These two grooves are of unequal size and termed the major and minor grooves. The difference in their size is due to the asymmetry of the deoxyribose rings and the structurally distinct nature of the upper surface of a base-pair relative to the bottom surface.

|

|

|

|

Figue

2. Specificity of DNA basepairing. The two strands of DNA are bound together via

hydrogen bonds between the nucleotide bases on each strand. The bonds are formed

by strict pairing between two complementary bases, A |

|

|

||

|

|

|

Figure 3. DNA replication conserves the nucleotide sequence. DNA is a double-stranded helical molecule bound together by the nucleotide bases contained on each individual strand. During cell division, two identical copies of the original parental strand are made by unwinding the DNA and then synthesizing a complementary second strand to make two identical new daughter stands. |

|

|

||

|

The double helix of DNA has been shown to exist in several different forms, depending upon sequence content and ionic conditions of crystal preparation. The B-form of DNA prevails under physiological conditions of low ionic strength and a high degree of hydration. Regions of the helix that are rich in pCpG dinucleotides can exist in a novel left-handed helical conformation termed Z-DNA. This conformation results from a 180 degree change in the orientation of the bases relative to that of the more common A- and B-DNA.

Thermal properties of DNA As cells divide it is a necessity that the DNA be copied (replicated), in such a way that each daughter cell acquires the same amount of genetic material. In order for this process to proceed the two strands of the helix must first be separated, in a process termed denaturation. This process can also be carried out in vitro. If a solution of DNA is subjected to high temperature, the H-bonds between bases become unstable and the strands of the helix separate in a process of thermal denaturation. The base composition of DNA varies widely from molecule to molecule and even within different regions of the same molecule. Regions of the duplex that have predominantly A-T base-pairs will be less thermally stable than those rich in G-C base-pairs. In the process of thermal denaturation, a point is reached at which 50% of the DNA molecule exists as single strands. This point is the melting temperature (Tm), and is characteristic of the base composition of that DNA molecule. The Tm depends upon several factors in addition to the base composition. These include the chemical nature of the solvent and the identities and concentrations of ions in the solution. When thermally melted DNA is cooled, the complementary strands will again re-form the correct base pairs, in a process is termed annealing or hybridization. The rate of annealing is dependent upon the nucleotide sequence of the two strands of DNA.

|

|

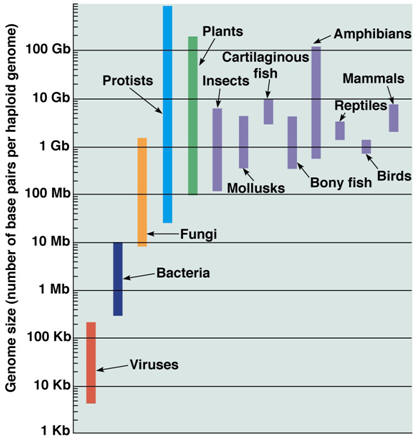

The genome The genome refers to the complete DNA sequence of an organism, which is enclosed in the nucleus of a cell (Table 1). In the human, there are 3 billion base pairs, which contain information that would more than fill a 500,000-page textbook. It is estimated that, in a single individual, if all of the chromosomes were joined end to end, it would reach from the earth to the moon about 8000 times. The actual length of the DNA from each cell is not apparent because the DNA helix of each chromosome exists as a compact, coiled structure stabilized by protein molecules, many of which are histones. The compact nature results in an increase in diameter, thus allowing the DNA to be visible by electron microscopy. The coiled, compact character of DNA enables all of the genetic information from a single cell to fit neatly into the cell’s nucleus, which occupies less than 10% of the total cell volume. The ~21,000 genes encoding a human being accounts for about 1% of the DNA, thus most of the DNA is nonprotein coding, but 80% of the human genome is thought to be functional. There are 46 chromosomes and each chromosome is a long continuous DNA molecule. The chromosomes vary in size, but even chromosome 21, the smallest of them, contains more than 50,000,000 base pairs.

|

|

Table 1. The human genome (completed April 2003)

|