Bioinformatics is the use of computer-based tools to assist in the analysis of biological data. The development of DNA microarray and sequencing techniques, and advances within these fields has allowed a vast amount of data to be obtained in a short space of time (most notably from the Human Genome Project). This has coincided with technological developments within the computer industry. Computer-based tools (in silico analysis) can be used in a variety of ways to analyse biological data, as illustrated below.

Similarity searches

Similarity searches are the most common bioinformatics-based tools and are located on many bioinformatics based websites e.g. the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). These tools allow the comparison of sequences that have no assigned function against ones that do. The websites typically contain a user interface allowing the user to input a sequence. The search algorithm then compares this sequence (unknown function) with all the sequences held in a database (known function) and assigns a similarity value. This allows a potential function to be assigned to the sequence in a considerably shorter time when compared to laboratory methods. The results of this type of search could potentially dictate future research avenues within the laboratory.

A comparison between two sequences must take into account certain points. If a query sequence will match with a higher degree of homology when a 'gap' is inserted, then the algorithm will perform the insertion. Scoring penalties are employed to reduce the number of gaps at different points along with length of gaps employed. All possible comparisons are taken into account and a final statistical value is given. This determines how similar the two sequences are. The hypothesis is that if the sequences are similar, then there is a good chance the function will also be. Similarity searches can be carried out for amino acid sequences as well as DNA sequences. In practise, both DNA and protein databases are searched and due to the degeneracy of the genetic code, different results may be obtained. As more organisms are sequenced and the databases become more reliable, so the results will become more accurate. The main role of genome databases is to distribute information for published or finished work. The databases are open to the public. Different types of databases exist that can be used for the analysis and functional characterisation of sequences. When considering DNA databases the main contributors are a combination of three sites, Genbank (US), EMBL (European), and DDBJ (Japan). Organism-specific databases are also common.

Performing secondary database searches, allowing conserved motifs to be identified, is a supplement to primary DNA/Protein database similarity searching. This type of search allows further characterisation of a sequence. Once similarity and secondary searches have been carried out, multiple alignment tools are used. Comparing multiple alignments allows the possibility of conserved sequences to be identified. These are also termed 'motifs'. Identification of such conserved sequences represents possible structural and functional similarities and also possible evolutionary links between sequences. This procedure may at first seem to be pointless if initial primary and secondary sequence searches have produced insignificant results. However, if a number of sequences are aligned simultaneously, important gene families (conserved domains) can be identified.

Functional assignment

Genome sequencing has led to a vast amount of information being deposited onto databases. One of the most important ways in which these sequences can be used is to try and assign function to them. Functional assignment is a large topic in bioinformatics and has many software tools that can be applied to this subsection of bioinformatics. There are two main techniques that can be employed to aid the process of functional assignment:

1. Use sequence-based methods, typically involving similarity search methods as described above.

2. Use structure-based methods, involving the use of bioinformatics software that predicts 3D protein structure from sequence. These tools allow users to input sequences into the program and then return a predicted structure that can be viewed in a viewing software and the hypothetical structures can then be compared to known structures held in a structure database with the aim of identifying structural homologues. Thus, with more and more sequences being made available, this approach is getting more and more attractive.

Phylogenetic analysis

Identification of similar sequences can also lead to phylogenetic analysis. Programs calculate the best possible phylogenetic tree diagram. Sequences containing homology could have diverged through evolution. Computational phylogenetic analysis can be a very useful supplementary tool for the characterisation of a sequence if used correctly.

Software-based tools for specific applications

An alternative bioinformatics-based tool is to use computer software designed for specific applications, e.g. to analyse microarray results in order to identify up- and downregulated genes within microarray experiments (quantification of spots on the microarray). Once the arrays have been scanned and quantification has been carried out, the next step is to normalize the data. Experiment normalizations are used to standardize microarray data to enable differentiation between real (biological) variations in gene expression levels and variations due to the measurement process. Normalizing also scales data such that one can compare relative gene expression levels.

Network and pathway analysis

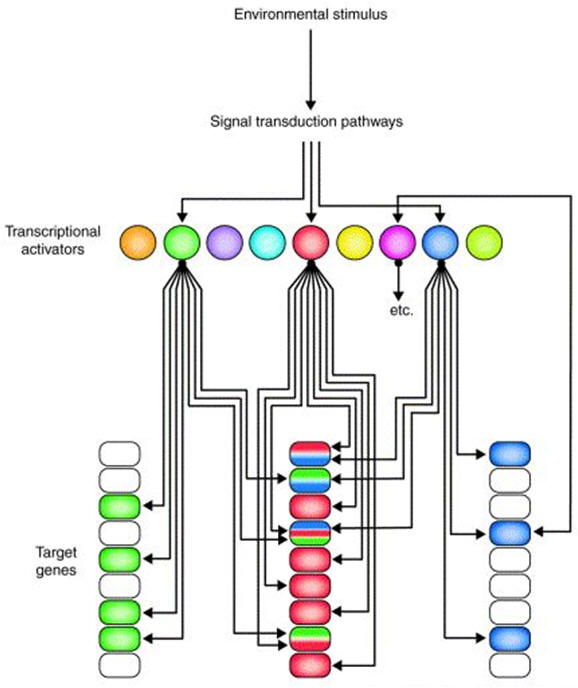

The biological system is a complex physicochemical system consisting of numerous dynamic networks of biochemical reactions and signaling interactions between cellular components. This complexity makes it virtually unanalyzable by traditional methods. Hence, biological networks have been developed as a platform for integrating information from high- to low-throughput experiments for analysis of biological systems. The network analysis approach is vital for successful quantitative modeling of biological systems. The advantage of network-based analysis methods is that, rather than using pathways as a whole, they identify subnetworks that are significantly differentially expressed.

Gene

expression regulatory network

Gene

expression regulatory network

See also: Molecular networks.