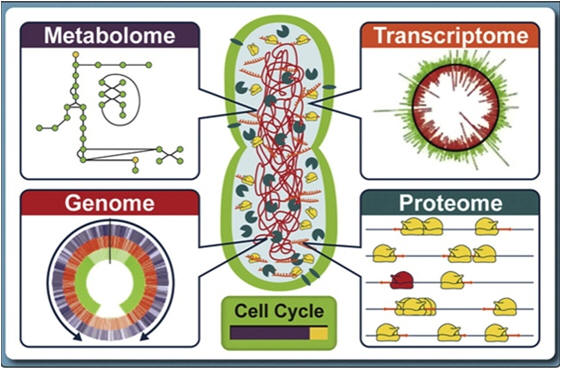

The avalanche of genome data grows daily. The new challenge will be to use this vast reservoir of data to explore how DNA and proteins work with each other and the environment to create complex, dynamic living systems. Systematic studies of function on a grand scale - Functional Genomics - will be the focus of biological explorations in this century and beyond. These explorations will encompass studies in transcriptomics, proteomics, structural genomics, new experimental methodologies, and comparative genomics:

-

Transcriptomics involves large-scale analysis of messenger RNAs transcribed from active genes to follow when, where, and under what conditions genes are expressed.

-

Studying protein expression and function--or proteomics--can bring researchers closer to what is actually happening in the cell than mRNA gene-expression studies. This capability has applications to drug design.

-

Structural genomics initiatives are being launched worldwide to generate the 3-D (three-dimensional) structures of one or more proteins from each protein family, thus offering clues to function and biological targets for drug design.

-

Experimental methods for understanding the function of DNA sequences and the proteins they encode (a more direct definition of Functional Genomics), including knockout studies to inactivate genes in living organisms and monitor any changes that could reveal their functions.

-

Comparative genomics—analyzing DNA sequence patterns of humans and well-studied model organisms side-by-side—has become one of the most powerful strategies for identifying human genes and interpreting their function. Having come a long way from its initial use of finding genes, comparative genomics is now concentrating on finding regulatory regions.

-

Metabolomics is the study of the metabolic profile of a given cell, tissue, fluid, organ or organism at a given point in time. The metabolome (that includes proteins, RNA, DNA, various substrates and small circuits of pathway networks) represents the collection of all metabolites (small molecules that are the intermediates and products of metabolism) in a biological organism.

-

Nutrigenomics applies genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics to human nutrition, especially the relationship between nutrition and health. Nutrigenomics is associated with the issue of personalized nutrition, since claims are being made that differences in genotype should result in differences in the diet and health relationship.

-

Epigenomics is the study of epigenetic changes (mainly DNA methylation and modification of histones; see under "cells and within cells, epigenetics") on a genome-wide scale.

-

Neurogenomics. The last ten years of the 20th century constituted "The Decade of the Brain". The time now seems ripe to begin a 21st century unification of genomics and neuroscience with one goal being to understand how only ~21,000 human genes contribute to the structure and function of an organ containing a trillion neurons with 1015 estimated connections. The full-scale application of genomics and bioinformatics technologies to brain research could lead to a new kind of systems neuroscience akin to the reconceptualization of "systems biology" in the genome era. Neurogenomics is the study of how the genome as a whole contributes to the evolution, development, structure and function of the nervous system. It includes investigations of how genome products (transcriptomes and proteomes) vary in time and space. Neurogenomics differs markedly from the application of genome sciences to other systems, particularly in the spatial category, because anatomy and connectivity are paramount to our understanding of function in the nervous system. Neurogenomics focuses on the contributions of genome-based research efforts in uncovering the molecular pathways and processes that underlie psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders in the mammalian CNS. Although it has long been thought that many diseases of the CNS in humans had a genetic component, the polygenic nature of these conditions made identification of specific genes challenging. The virtual completion of the human and mouse genome projects combined with advances in transgenic mouse technologies now affords the possibility of integrating often-times quite disparate fields of research to provide unique insights into the molecular basis of aberrant CNS function. Neurogenomics areas include:

-

Model organisms of psychiatric disorders

-

Network genetics and applications to behavioral phenotypes

-

Genetics of neurodegenerative disorders

-

Gene expression atlases of the brain; see under Generation of gene expression atlases of the CNS

-

Genome-wide screens for genetic risk factors for human psychiatric disorders; see under Genetic variations: SNPs and CNVs and Genome-wide association studies (GWAS)

-

Comparative Neurogenomics

-

-

Neurophenomics. Following the sequencing of the human and mouse genomes, the next major step is to assign a function to each of the identified genes. The currency of gene function is the mutation. The majority of mutations that have been found in humans is single-base pair mutations. Phenotype-driven approaches are important for bridging the gap between gene identification and understanding gene function. Knowledge of the genetics of nervous system function and regulation of behavior will lead to improved understanding of normal and abnormal brain function and behavior, enhanced diagnostics, and more effective therapeutics. Forward genetic strategies are being used to identify genes involved in nervous system function and behavior. Thus, while various genetic engineering strategies provide information about gene function through knockout technologies, to best model human disease mutagenesis programs that employ single-base pair lesions are desirable and often focus on the use of N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) to induce single-base pair lesions in the genome and allow for an unbiased approach which involves screening potentially mutant lines for a host of neuro-behavioral, -physiological, and -anatomical phenotypes. For instance, ENU-mutagenized C57BL/6J mice are being used to identify neurobehavioral mutations in five domains (the phenotypic screens focus on neuroendocrine and behavioral responses to stress, learning and memory, psychostimulant response, vision, and circadian rhythm), and a three-generation breeding scheme to produce homozygous mutants to recover both recessive and dominant mutations. Whole-genome and regional approaches as well as large-scale mutagenesis programs are thus being used (see http://www.tnmouse.org/neuromutagenesis/). This field is called Neurophenomics. Furthermore, in this endeavour, issues such as administration, bio-informatics, power of phenotypic screens to detect behavioral outliers, and identifying the mutant gene are important. A further interesting contribution in this area concerns a saturation screen of the druggable mouse genome to identify novel drug targets for neuropsychiatric disease. For this, a large-scale phenotypic screen in mice has been undertaken to identify genes that regulate neuropsychiatric behavior. The screen is based on the production and phenotypic analysis of mouse knockouts of all genes that are members of gene families whose protein products are considered to be tractable for drug development (see figure below). The knockout animals are subjected to a behavioral screen that includes tests for anxiety, depression, psychosis, pain, circadian rhythms and cognition. To date more than 1,250 genes have been knocked out and screened with a goal of completing 3,750 additional genes. Another aspect of Neurogenomics is the need for model organisms intermediate between mice and humans that can be investigated using genetic approaches. Genome mapping in non-human primates provides these models, and will be particularly important for the investigation of brain and behavior. Such mapping and sequencing projects are underway in a wide range of primate species, including the vervet monkey. Several decades of studies in well-characterized vervet colonies have demonstrated heritability for a wide range of behavioral phenotypes. These highly inbred colonies are equivalent to human population isolates, and are thus particularly powerful for genome-wide genetic mapping of such phenotypes. Indeed the vervet offers an ideal test for a phenomic approach to the investigation of complex traits; the phenome is the comprehensive representation of phenotypes, and a phenomic approach to genetic mapping involves simultaneous analysis of the whole phenome by performing genome-wide genotyping of an entire study population. For the investigation of brain and behavior, the evaluation of the vervet phenome can include, for example, neuroimaging, gene expression profiling, and pharmacologic interventions, in addition to existing behavioral assessments.

-

Pharmacogenomics (that combines medicine, pharmacology and genomics) tries to understand the correlation between an individual patient's genetic make-up (genotype) and their response to drug treatment. Some drugs work well in some patient populations and not as well in others. Studying the genetic basis of a response of a patient to therapeutics allows drug developers to more effectively design therapeutic treatments. Thus, through pharmacogenomics, drugs might one day be tailor-made for individuals and their conditions, allowing prescription of the most effective drug dosage and a reduction of unwanted side effects. Pharmacogenomics is therefore the use of genetic information to predict drug response. The term drug response includes two facets: drug effectiveness (efficacy) and drug side effects. It is estimated that, on average, as much as forty percent of the medicines that individuals take every day are not effective. In fact, for certain medications, the estimate of non-effectiveness is well over 50%. Every drug simply does not work for every individual and many people are exposed to the problematic side effects of drugs while receiving little or no benefit. Pharmacogenomics tries to identify people whose genetic profiles or "bar codes" predict that they are inappropriate for a given medication, whether due to poor efficacy and/or adverse side effects. Pharmacogenomics allows physicians to prescribe with greater confidence, and pharmaceutical companies to more effectively target drugs where they will do the most good. The current one-size-fits-all approach to medicine will be augmented increasingly by diagnostic analysis that, for many drugs and many patients, will validate the appropriateness of certain medications before they are administered. One approach to pharmacogenomics is to directly study the genetic component of the problem (the DNA itself) to understand the way in which variations in DNA sequences contribute to phenotypic traits such as common diseases and drug responses. See also under "Pharmacogenomics".